On a summer morning, strolling through the old streets of George Town in Penang, moss covers the stone pavements after the rain, and the air is filled with the aroma of laksa and coffee. In this moment, it feels as though one has stepped into an old South Seas film directed by Ang Lee.

Close your eyes, and you’re transported to Singapore’s Marina Bay: neon lights, towering buildings, order and efficiency intertwined like a painting. Penang and Singapore are like two ‘twin sisters’ with strikingly similar objective conditions—both part of the British colonial legacy, both sharing Chinese cultural heritage and the advantages of strait trade—yet they have taken two entirely different paths to prosperity.

‘Just across the strait, is it really just a matter of having a Lee Kuan Yew?’

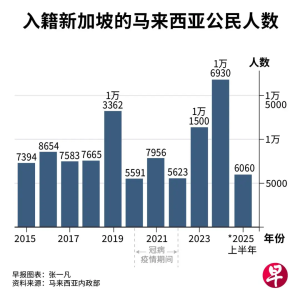

Meanwhile, in the first half of 2025, 6,060 Malaysians renounced their Malaysian citizenship to become Singaporean citizens. Since 2015, this number has accumulated to 98,318, averaging nearly 10,000 new citizens per year. Is this driven by the times, or the institutional charm left by Lee Kuan Yew?

I. The Flow Behind the Numbers:

Why are Malaysians choosing Singapore?

1. Official data on naturalisation trends

Malaysian Home Minister Saifuddin Nasution responded in writing to the Lower House in early August 2025:

As of the end of June 2025, 6,060 Malaysians had renounced their citizenship and naturalised in Singapore. Since 2015, the cumulative total has reached 98,318, with 16,930 in 2024 alone, marking a new high in nearly a decade. In 2019, there were also 13,362 naturalisations. Although there were fluctuations before and after the pandemic, the overall number remained between 5,000 and 17,000 annually.

Earlier data also shows that from January 2020 to February 2025, 52,225 people have renounced their Malaysian citizenship, averaging approximately 842 people per month making this ‘life-changing decision.’ Is this migration an “escape” or an ‘upgrade’? It is worth further investigation.

Source: Lianhe Zaobao

2. The Multiple Attractions of Choosing Singapore

① Abandoning the old identity to enter a modern nation with a superior system

Neither country recognises dual nationality, so naturalising in Singapore means completely severing ties with the past and embracing a new identity. This choice is filled with ritual and symbolic meaning.

② Transparent policies and predictable approval efficiency

According to data from the NPDT and ICA, 23,472 new citizens and 34,491 permanent residents were granted status in 2023. This represents a slight increase compared to the previous five years, reflecting a stable capacity for acceptance.

ICA states that most PR applications are processed within six months; applying for citizenship requires at least two years of PR experience. This predictable path is more appealing to many than the unknown.

③ CPF social security system support

Both Singaporean citizens and PRs are required to contribute to the CPF, which helps individuals save for life events such as housing, medical care, and retirement. The MediSave, Ordinary Account, and Special Account can be flexibly managed for medical care, housing, and investment purposes.

For example, the Basic Healthcare Sum at age 65 is S$71,500, covering basic medical needs.

④ Significant Differences in Education and Healthcare

Singapore citizens pay significantly lower tuition fees at government schools compared to PRs or foreign students. For example, primary school tuition is approximately S$6.50–13 per month, while foreign students pay approximately S$490–888. The healthcare subsidy system (Medifund) is well-established and serves as a crucial support for families facing economic pressures.

Systems such as the Edusave Scholarship and childcare allowances offer families looking to the future more possibilities.

⑤ Passport accessibility and employment stability

Singapore passports rank highly globally, offering high visa convenience. The job market is relatively stable, with no reliance on work permits like the Employment Pass (EP) or S Pass, allowing for career development without concerns.

These factors collectively form the rational basis for Malaysians choosing to relocate to Singapore, also signaling an aspiration for upward mobility.

Source: Lianhe Zaobao

II. The diverging destinies of twin sisters:

It was Lee Kuan Yew, but not just him

1. Similar historical paths, yet divergent outcomes

Penang and Singapore were both British Straits Settlements, sharing similar geographical and ethnic compositions: high Chinese populations, similar cultural atmospheres, and comparable maritime economic origins. However, after the federation dissolved, the trajectories of the two cities diverged completely:

Singapore was forced into independence, adopting a ‘startup nation’ survival model.

Penang remained a ‘branch office’ within the Malaysian Federation, prosperous yet lacking the comprehensive planning and control of a sovereign state.

2. Lee Kuan Yew: The Entrepreneurial Coach of Risk, Survival, and Institutional Design

In 1965, Singapore became a city-state with ‘no room for retreat.’ As the ‘founding CEO,’ Lee Kuan Yew wielded absolute power and a sense of mission. He established a governance model characterised by high efficiency, the rule of law, and a focus on talent, propelling Singapore to become a global financial and trade hub.

Penang, though endowed with artistic flair and regional cultural influence, faced resource allocation tilted toward Kuala Lumpur and Port Klang under the federal system. Leaders were mostly ‘professional managers’ who had to comply with budget and policy arrangements, lacking the ‘breakthrough’ leadership needed to reshape the city’s destiny.

This is not to diminish Penang’s efforts, but to illustrate that choices and institutional frameworks determine a city’s ceiling.

Source: Internet, remove if infringing

III. Institutional Details:

Singapore’s ‘Predictable Success’ System Analysis

1. ICA’s Approval Process and Efficiency Guarantees

According to the EDB website, individuals aged 21 or older with two years of Permanent Resident (PR) status may apply for citizenship.

The Global Investor Programme (GIP) offers a fast-track pathway for high-net-worth investors; students may submit electronic applications via Singpass.

ICA also emphasises that approval depends on whether applicants demonstrate ‘integration’ and ‘commitment to putting down roots,’ reflecting a balance between quantitative criteria and subjective assessment.

2. CPF: A Three-Pronged Security Mechanism

CPF includes sub-accounts such as the Ordinary Account (housing, insurance, education), Special Account (retirement investment), and MediSave (medical expenses). At age 65, the Basic Healthcare Savings (BHS) amount is S$71,500, ensuring basic needs are met. Excess amounts can be transferred to investment accounts to participate in the CPF Investment Scheme.

Additionally, CPF helps accumulate wealth and alleviate retirement anxiety, embodying the core values of the new citizenship system.

3. Differences in Education, Housing, and Taxation

Education: Citizens enjoy significant preferential policies, such as annual Edusave subsidies, scholarships, and university tuition subsidies;

Housing: HDB flats are prioritised for citizens, while PRs or non-citizens receive lower priority and smaller allocations;

Taxation: Singapore implements a progressive tax system with relatively low rates, such as a 15% tax burden for an annual salary of S$120,000, making financial planning more manageable.

These institutional details constitute the tangible ‘benefits’ of citizenship—not just prestige, but practical, on-the-ground support.

Source: MOE

4. Penang: A cultural city,

or a potential second path for the future?

Penang remains the ‘Little Paris’ in the hearts of many culture enthusiasts: vintage old streets, UNESCO World Heritage sites, and the laid-back lifestyle of Southeast Asia. However, in modern national governance and resource allocation, it lacks a strong strategic position and industrial influence.

If it were willing to upgrade from a ‘cultural slow city’ to a regional innovation hub, there might still be room for growth. But as talent shifts toward higher well-being and more stable development, a laid-back lifestyle is no longer the primary draw.

Source: Lianhe Zaobao

5. Individual Perspective:

Two Malaysians’ Stories of Naturalisation

Case 1:

Yalin, from a Chinese family in Penang, worked at a Singaporean tech company after graduating from university. After two years as a Permanent Resident (PR), she applied for citizenship. Once her main applicant status was converted to citizenship, her children gained access to quality schools, and the Central Provident Fund (CPF) supported their future education and retirement planning, prompting her to unhesitatingly renounce her Malaysian citizenship.

Case 2:

Ali, a Malaysian civil servant, found an opportunity at a Singaporean financial institution. He valued career stability and passport freedom: as a citizen, he would not need to renew his work permit every two years. After residing as a PR, he prepared to naturalise, and the investment appreciation features of the CPF also showed him the potential for long-term capital accumulation.

Their stories, like those of countless immigrant families, reflect a pragmatic path driven by practical considerations, rather than blind admiration for foreign cultures.

Source: Lianhe Zaobao

6. Urban Impact and Future Outlook:

How long can the two cities continue to interact?

For Singapore: Stably attracting high-quality talent helps mitigate the challenges of an ageing population and demographic structure. The NPTD 2024 report notes that the absorption rate of PRs and citizens is slightly higher than the previous five years (approximately 22,400 citizens and 32,600 PRs annually), which helps address the issue of an ageing citizenry.

For Penang: Talent outflow may exacerbate the solidification of educational resources and economic opportunities. Without policy innovation and strategic reorientation, it may be increasingly labelled as a ‘tourism and cultural zone’ in the future.

ASEAN regional trends: As globalisation and talent mobility intensify, an increasing number of young people in Southeast Asia will choose countries with institutional advantages and clear development prospects. While Singapore maintains its institutional advantages, Penang needs to redefine its development path to attract people willing to invest in its future.

Source: Lianhe Zaobao

Conclusion: It’s not just one person who is lacking, but an entire set of path choices

Penang and Singapore are not lacking a Lee Kuan Yew, but a set of systems, strategic vision, and path choices:

Singapore chose a national strategy of survival-or-death entrepreneurship, building efficient governance, a welfare system, and global connectivity;

Penang is deeply rooted in culture, but without breakthroughs at the top, it can only dance in the ‘beautiful memories’ of the past.

When talent asks themselves, ‘Where can I find a more stable, freer, and more opportunity-rich future?’ sentiment without a value-added path can only be preserved, not retained.

This cross-strait ‘twin-city story’ reminds us: choice matters more than effort in determining direction. Penang can remain charming, but if it wants to regain its leading role, it must make a bold choice once again.

Note: Reference materials sourced from Singapore’s ICA, MOM, NPTD, CPF, EDB, MOE, IRAS, MAS, Lianhe Zaobao, Malaysia’s Ministry of Home Affairs, and comprehensive public news reports. Reproduction must credit the source; contact for removal if infringing…..